На првата годишнина од подкастот „Обични луѓе“, епизода број 17 која раскажува приказна која долго чекала да биде обелоденета. За американскиот фотограф Нил Фолберг, кој во далечната 1971 поминал неколку месеци во Македонија, и од тука понел повеќе од 400 ролни филм. Дури сега, педесет години по нивното создавање, тие се објавени во форма на книга.

Верзија со македонски/англиски титл на Youtube

Забелешка: „Обични луѓе“ е подкаст наменет за слушање. Во него е вграден голем труд за монтирање, музичка илустрација и течна аудио нарација. Транскриптот е наменет само како помошно средство, особено доколку архивските материјали се со понизок квалитет. Во сите други случаи ве поттикнуваме да ги слушате, а не да ги читате епизодите. Ви благодариме.

С2Е7 Транскрипт

Intro

Васка Илиева – „Ајде ред се редат кочански сејмени“ (од компилацијата „Билјана платно белеше“, ЛП, издадена 1971 oд Југотон)

[Neil Folberg]

Folk music always spoke to me. This is how I came to Israel too. It’s the same thing. I loved the music, it spoke to me, it tells a story. And it gives the spirit of the people in a way no other music can. It is not contrived; it comes from the people. And it was that music that drew me to the Balkans in general and to Macedonia in particular. There was something about the Macedonian music that was so strong and vital that I felt there had to be something deep and beautiful there to see. And I go by my feelings.

[Ilina]

Ова е Нил Фолберг, денес 71-годишен американски фотограф, кој живее во Израел. На неговите прекрасни фотографии од Македонија од 1971 неодамна налетав случајно, на интернет. Првата помисла беше – како е можно никој тука да не ги видел, цели 50 години? Зошто до сега немало изложба, студија, каква и да е промоција на постоењето на една ваква вредна збирка?

(Common People)

Jaс сум Илина Јакимовска. Во оваа епизода од подкастот Обични луѓе ќе се обидеме да ја раскажеме оваа долго одложувана приказна. Останете со нас.

(музиката продолжува)

[Ilina]

Пред педесет години Нил бил млад студент по општествени науки, со силен интерес кон уметностите. Но во тоа време не било баш лесно да се мешаат дисциплините.

[Neil]

I was a student already at the University of California, at Berkeley, I’d been studying sciences and I’d decided to switch to, essentially, photography. But as I described, it was an academic University, this wasn’t a place to study art. But it had other strengths, it had a…like a good department of Slavic studies, including an excellent instructor in Serbo-Croatian, not Macedonian, but аn instructor in Serbo-Croatian, of course Macedonia was at that time a part of Yugoslavia. And I got interested in the whole region through folk music, I always liked folk music.

[Ilina]

Нил го имал посетено Балканот претходно, престојувајќи месец и пол кај семејство во Сплит, Хрватска. Со пријател патувале низ регионот. Maкедонија го маѓепсала – за него тоа било земја на едноставни, чесни луѓе, каде сакал да се врати. Но за тоа морал да смисли добар план.

[Neil]

When I decided to move to photography I was looking for a project. I felt that the best thing you could do is to do a project. And Berkeley at the time was in a midst of a student revolution, you know about this, they were interested in radical politics. I was not interested in radical politics, but I was interested in sort of a comprehensive view of education where it wasn’t just one thing that you studied, but everything together, to make connections. So, when I decided that I was to make a photographic project, my first thought was, okay, I’d like to do something in Macedonia.

Тhe University opened up a program where you could make your own individual curriculum. It wasn’t even an individual major within a specific college, you could actually, essentially create a college. And something that wasn’t part of a university discipline. And I’d heard about that course, I signed up for it and by that time I was connected with, I’d been studying privately with an American photographer Ansel Adams, he is very famous, very well known, and there was another photographer, of tremendous stature, less well known, at Berkeley, within the department of architecture and design: his name was William Garnett. So I said why don’t we make a proposal, that I should do a series of photographs in Yugoslav Macedonia, differentiating it between the parts that were in Bulgaria and Greece. I wasn’t capable of dealing with so much at one time, and that would’ve been politically difficult as you could imagine.

[Ilina]

Со комбинација на добар предлог, солидни референци и чиста среќа, проектот на Нил е единствениот од педесет кој е одобрен. По долга административна процедура на добивање работна дозвола, преку тогашниот југословенски конзулат во Сан Франциско, тој се качува на авион, најпрвин до Белград, потоа до Скопје. Во тоа време кога се слетувало на скопскиот аеродром, пистата најпрвин морала да биде расчистена од овци.

[Neil]

The first thing that I did when I got there, I had met a family the first time I was in Macedonia, I had met a family there and Kosta Bozinovski, who picked me up hitchhiking. He was a government driver and he had a government car and I was hitchhiking I think from around, we come down from the mountains from Galichnik, and we were on the main highway and we were heading towards Skopje. And he picked us up.

[Ilina: With a government car?]

With a government car, which I think he was not supposed to do. I guess we looked interesting and he was a very friendly man, so he took me to Skopje and he invited me to stay there and he said if you ever come back you can come to stay with us. He gave me the address and I think I must have stayed. I don’t know where I stayed for the first couple of nights, but then I went to look for him and asked if I could stay a while till I find a more permanent place to stay, so the Bozinovski family took me in.

© Neil Folberg

[Ilina]

Семејството Божиновски живеело во пост-земјотресна барака, во која немало многу место. Сепак како добри домаќини му ја дале спалната а тие се преселиле во кујна. Подоцна Нил изнајмува соба со помош од некој „од горе“, веројатно за властите да го имаат полесно на око.

Во фокусот на Нил се нашле луѓето врзани за земјата, селата и малите градови. Списокот на места кои ги посeтил ги вклучуваат Битола, Кратово, Струмица, Делчево, Прилеп, Демир Капија…Галичник, Булачани, Маврови Анови, Косоврасти. Импресивен список дури и за млад патник низ мала земја. На времето ова значело многу возење со автобус, но и многу пешачење, како искусен етнолог.

[Neil]

From there I started just to explore the area, wherever I could get to on bus or by walking. I did a lot of walking and a lot of riding the buses. Everything was an adventure, I mean you could start anywhere…I had specific goals, I tried to get inside people’s homes, I was trying to photograph at least some representative sample of the population and I was interested in speaking to just ordinary people.

I wanted to make a coherent statement, a visual statement and so I came back to that idea that I started with, the idea of people on the land and I sort of neglected the photographs that I made in a more urban setting, in Skopje, which was of course the only real city in Macedonia. And I went and visited also all of the little towns, and I didn’t develop everything as much as I would have liked to, but I was fascinated by the relationship between the villages and the market towns where people took their produce, where they purchased the things that they couldn’t grow or create for themselves, and I probably, if I had been there longer, if I had more time, I would have followed that connection little bit more closely.

© Neil Folberg

[Ilina]

Бирократијата и надзорот од властите продолжиле. Сепак, Нил не го доживеал ова како малтретирање.

[Neil]

The thing that was nice about all of Yugoslavia was it was a very human, easy place and people were basically hospitable, even the officials, even when they became very difficult, never lost that human touch. So, sometimes I had very humorous encounters, sometimes they were difficult, and even occasionally a little bit scary, but that humanity was never lost. So, I had to have permission. You know in those days you had to have permission to photograph everything. If you wanted to photograph ‘spomenici’, what they called cultural monuments, then you had to have permission from the Government. If you wanted to photograph in the churches, you needed permission on the religious basis, and you had to have permission from each of the different administrative authorities. And, if I wanted to photograph people on the street, thеn I had to have permission from the Government to be photographing. They expected tourists to go and photograph tourist sites, and you could make photographs of people in, maybe, Bit Pazar, and you could make photographs here and there on the street, but if you started getting too serious about it then the police started asking questions. Usually, they didn’t ask questions they just shouted “Zabranjen” and told you, you can’t do it. Or told you “Verboten”, more often, more likely, assuming that every tourist with a camera is a German spy.

[Ilina]

Ова е приказната од аспект на властите. Но што е со „обичните луѓе“? Каков впечаток имал странецот за секојдневниот живот во тој период, за кој денес во Македонија не е можен консензус?

[Neil]

That’s a very interesting question. Because you know I was an outsider, sometimes an outsider has an advantage, not a total outsider, I was familiar with the culture, I’ve studied some anthropology, I’ve studied some history, I spoke at least one of the languages of Yugoslavia, and I picked up some basic Macedonian. So, I was an outsider with insight, I’d like to think, and I can tell you that despite the fact that it was little bit oppressive, that the state security agencies were a bit heavy-handed with me, and I imagine they were more heavy-handed with citizens of Yugoslavia. So, I can’t say it wasn’t a little bit oppressive, but I didn’t see that people were too intimidated in general.

Maybe if you were a very political figure, and your whole life was politics and human relations, or if you were a Macedonian nationalist, and I met several Macedonian nationalists, then maybe you would’ve found it very oppressive. But in general, I didn’t feel that the state, the SFRY at that time, in 1971, was all that oppressive. It was open, it was comfortable, the standard of living in Macedonia was somewhat lower than Serbia and Croatia, but I didn’t feel it was bad. It was very pleasant, everything was easy. There was abundance, there was plenty of food, I didn’t see that people were starving, you know you walk down the streets in the USA and there are people on the streets. I didn’t see that in Macedonia. The standard of living was not at that high American standard that I was living more or less, I was a student but we had everything, my parents were fairly well off, there wasn’t that almost ridiculous abundance, but everything that was necessary was there. And people were outspoken, people told me what they thought, they weren’t afraid to speak to me.

So, I felt like Yugoslavia was a nice place. I was sorry when it broke apart, I was sorry when it broke apart because I was sorry for the Serbians and the Croatians that got into that terrible war, and there were so many atrocities, I couldn’t dwell on it, I couldn’t imagine it, it hurt me so much to see it from the side, I shut it out from my mind. And I was glad that Macedonia managed to stay, it seems, mostly out of it.

© Neil Folberg

[Ilina]

Категоризирани, сликите на Нил од Македонија во 1971 покриваат неколку теми: селани и стопански активности, пазари, празници и прослави и портрети. Сите се во црно-бела техника. Зошто?

[Neil]

Sometimes the two-dimensional object, the artistic creation, has a good deal more power than the original item, or event or subject. And I don’t know exactly how that works. It must be something about the way that, as if art or a photograph can take the essence of an experience, or a place, and translate it into something that’s more easily accessible to the human imagination. So, without trying to analyze that, there’s something about black and white photography which is more abstract, that places something on a level where it’s just tonalities of black and white and gray. And it sometimes allows the essence of something to come out better than color, which might be in some ways distractive. So, at the time, I mean I worked a lot in color, I haven’t exclusively worked in black and white, but I felt that black and white was suited to that subject. There’s also an American tradition of documentary photography from photographers like Dorothea Lang or Walker Evans, and it’s a long list. And that tradition carries over into other places as well. But I think I was connected to that tradition as well.

[Ilina]

Технологијата на тоа време, како и опремата со која располагал, го одредила и фотографскиот и човечкиот пристап кон луѓето на сликите. Фактот дека камерата била впечатлива и подобро функционирала на статив, значело дека Нил не бил невидлив.

[Neil]

I was a student. I didn’t have a lot of equipment. I couldn’t have a big budget. I brought one camera, one lens, it’s what I had. I started out with a Practica 6×6, I like the medium format, I couldn’t afford anything better at the time, I bought this East-German camera, it had good optics, but mechanically it was not so nice. I started out with that, I had trouble with it.

So I went to Thessaloniki, and looked for a better camera and ended buying a Rolleiflex. It’s a medium format camera, it’s big, it has a presence, it requires… it’s better with a tripod, so it wasn’t just a camera that you just snap away with and make thousands, and thousands, and thousands of photographs. It requires some kind of thought process. Pre-visualization, where you anticipate what you want to photograph, you concentrate on it and instead of making a hundred or fifty photographs, now [for] people with the digital there’s no limits, people can, they can put thousands of pictures on a card – I had 12 pictures on a roll of film. And I had to make that count. One, because it was expensive, and two, because you can’t take that many photographs. You have to think about it, it’s a contemplative process, making photographs with a larger format. That meant that when I approached a person they were well aware of me, I wasn’t just sneaking around making candid photographs. I was a presence. And look, I was a strange presence, I looked different. Everybody could see that I wasn’t from there.

I would be in a public place, I wouldn’t be invisible, people saw me, and often I would set up a tripod in a public place and just wait for something to happen. Just wait to see who came to me. Who wanted to talk, who was curious, and there were people who couldn’t be bothered, and the police were always there. But I thought, at the time, that I was making photographs that were objective. I was looking at the Macedonian society,and I was doing my best to give a balanced, objective view of it. If it wasn’t comprehensive, it was because I didn’t have enough time to delve into it, as deeply as I would have liked to.

[Ilina]

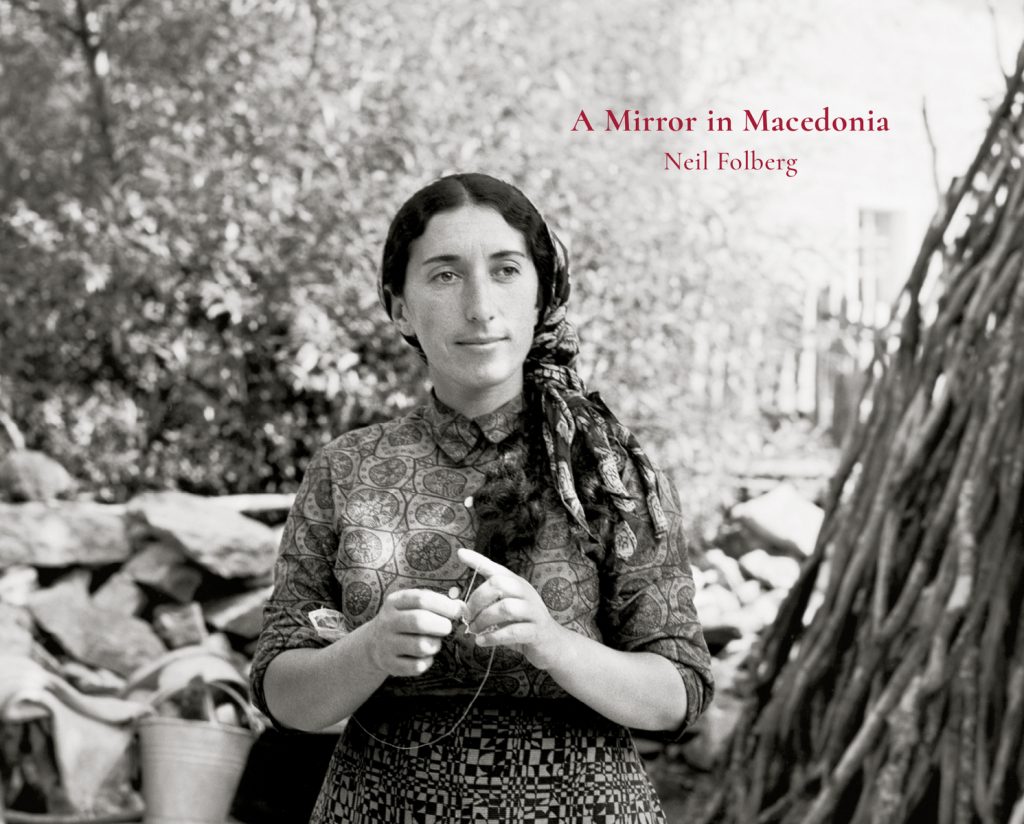

Мојот контакт со Нил се случи во интересен момент, кога долго одложуваната книга со фотографии од неговиот проект во Македонија е во подготовка конечно да ја види светлината на денот. Во преговори сега е издавање и на верзија на македонски. Насловот на книгата е симболичен.

[Neil]

I was trying, as I said, to be objective. But in the end, I look back at those photographs from 50 years ago in Macedonia, I’m not only looking back at Macedonia, I’m looking back at myself. And that was an amazing discovery. I thought that these were photographs of the Macedonians, of the land, and that it was somehow divorced from me or at least removed from me, like I was a window onto the culture, the land, the place, the people and I was doing my best to make myself invisible. But for myself, when I look back 50 years, and I look at these photographs, even though I am not the subject of the picture, I can see myself looking back from this mirror. And that’s why I call the book “А Мirror in Macedonia”. Because, I discovered that it was me looking back. And just like those photographs are frozen in 1971, these people are from 1971, the scenes are from 1971, the physical culture is from 1971, and I too, I’m frozen in those 400 rolls of film, somehow I’m pictured there, kind of like a specimen that’s been preserved.

I can’t tell you how deeply this experience affected me. You know, what happens is that when you step outside of yourself, you do this all the time, this is your profession, you step outside of yourself, and you’re going into somebody’s else’s world, and trying to imagine what it’s like for them, what they are thinking, what they are seing and you know, I think we’re are capable of doing it. I think you can step into somebody else’s world, you can’t ever leave yourself entirely, but you can use your imagination and know what it feels like to be in that person’s place. And I don’t think that’s impossible. That’s the essence of communication.

[Ilina]

Значењето на овие фотографии сепак не е само историско, етнолошко или естетско. И не е интимно само за нивниот автор. Родена сум во 1971. Стара сум исто колку и овие фотографии. Јас и тие истовремено сме се нашле на овој свет. Така, гледањето во нив поттикнува чувство на изминатото време. А освен фотографии, Нил сочувал и голем број други материјали, белешки, писма. И аудио фајлови. Еден од нив е снимен во Лазарополе на Илинден, мојот именден и роденден.

(архивска музика)

[Ilina] I’m kind of jealous of your life, you know (both laughing) Really, I don’t know if you are aware that you had, from my perspective, you had a very rich artistic, I don’t know about private of course, but in terms of artistic life you had very interesting company first of all, context, and also opportunity to travel. So I think it’s amazing, the whole story of it. Especially because it relates to Macedonia, of course, but not only.

[Neil] Well, I feel like my life has been very, very special in that sense because I was able to get out, look around and see other people. And the camera is an interesting tool, because it kind of puts you in another status. You can walk into other people’s lives and they accept you, you can walk into other people’s culture and they don’t think anything weird about you being interested, making photographs, if you [would have] started poking around and asking questions they might get a little bit suspicious, but people are used to [the] camera and it is a kind of entry tool. And if you’re curious and you have an imagination, then the possibilities are sort of limitless.

[Ilina]

Во изминатите 50 години Нил Фолберг самиот ги има поместувано уметничките граници, испробувајќи се во други светови. Неговите дела вклучуваат фотографии од пустините и духовните наследства на Израел, Египет и Јордан. На историски синагоги низ светот. Поврзувања со други визуелни уметности, како францускиот импресионизам. Книга со наслов „Небесни ноќи“, пак, ги претставува небесата и ѕвездите, и претставува промена на фокусот на неговиот интерес – од луѓето и нивните земски преокупации, кон огромниот космос. Ова има врска и со едно негово хоби.

[Neil]

Ever since the period when I was at Berkeley I’ve been sort of interested in astronomy, so I think that’s my hobby. I am an amateur astronomer, I have a small observatory in my house, and I go out and look at the stars. That’s my escape now especially during this year of Corona, which we’d experienced all over the world, we’ve all been confined to the places where we live and maybe inside, not outside so much. So I can walk out on my porch, open up my observatory and go 15 million light years away to some galaxy in ten minutes.

[Ilina]

Ако погледнете во галаксија која е оддалечена 2 милиони светлосни години, вели Нил, вие всушност гледате 2 милиони светлосни години во минатото. На истиот начин, ако гледате во фотографија која е стара колку едно трепнување во небесно време, би можеле да видите не само какви биле нештата вистински, туку и како можеле да испаднат.

(Common People music)

[Ilina]

Јас сум Илина Јакимовска. Аудио монтажа – Бојан Угриновски. За целосен транскрипт и фотографии посетете ја нашата страница, obicniluge.mk. Верзија со англиски титл е поставена на јутјуб каналот Обични луѓе.

Апдејт: По објавувањето на подкастот, книгата на Нил Фолберг беше преведена и издадена на македонски од страна на Арс Ламина. На 19.06.2023 авторот и сопругата беа присутни на нејзината промоција во МКЦ, каде неочекувано се појави и внукот на жената на насловната страница.